There are many differences between woodworking in today’s machine age and the 19th century. Contemporary carpenters and furniture makers rely on drawings, dimensions, and precise measurements to help them plan and build things. Before the Industrial Revolution, however, things were very different. 19th century house joiners certainly did rely on pattern books, but these books didn’t contain measured plans with precise dimensions for Federal or Greek Revival doors, windows and moldings. Instead, these pattern books had drawings of various elements with proportions.

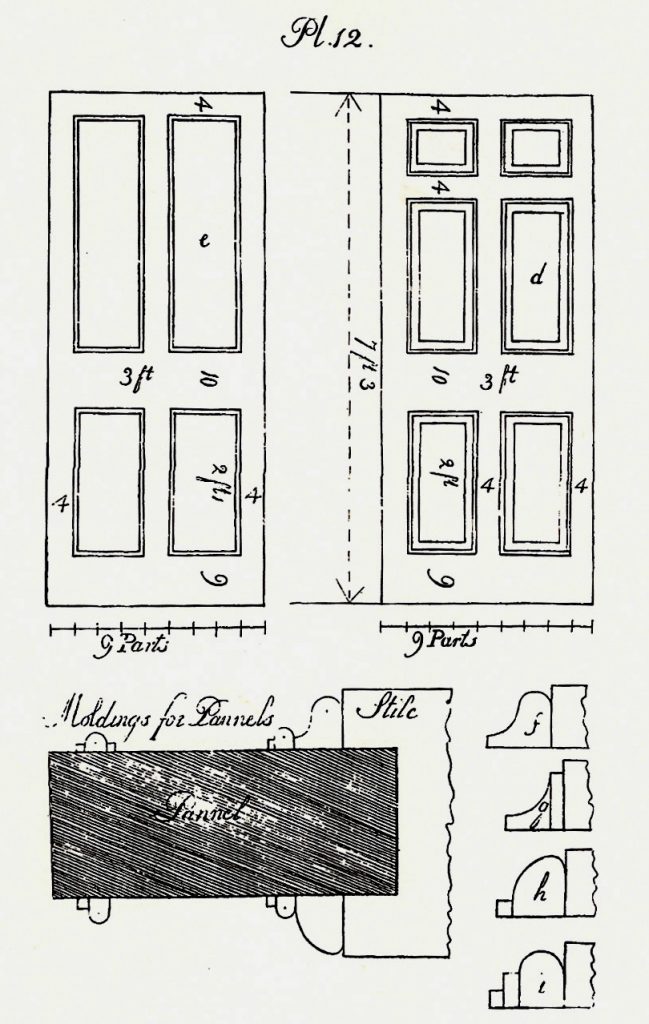

What do I mean by this? Lets look at a 1797 plan book by Asher Benjamin and see. If you wanted to build an interior door today you would buy a set of measured drawings for a 2/8, 2/10 or 3/0 door which would give you the standardized width of the stiles, bottom, top and lock rails, dimensions for the molding, etc. If you look below at a plate from Benjamin’s 18th century plan book, you will see that the drawings are far simpler.

The first thing to notice is the series of 9 marks beneath each door. Rather than dimensions, Benjamin instructs the joiner to divide the width of the door opening into 9 equal parts or steps of a divider. If you are building a 3/0 door, which is 36 inches in width (as in the example Benjamin gives here), you would have 9 parts or steps of 4 inches each. On the 4-panel door each stile, muntin and top rail is one part wide (or 4 inches), the bottom rail is 1 1/2 part wide (6 inches) and the lock rail is 2 1/2 parts wide (10 inches).

The genius of this approach is its simplicity and flexibility. If your door opening is an odd size like 2/9, 2/11 or 3/2 (as is common on older homes), you simply step off 9 parts on the door opening’s width with a pair of dividers and there you have your base measurement. You then use the dividers to lay out the width of the stiles (1 divider step or part), the dimension of the bottom rail (1 1/2 divider step) and so on until you have your stock ready to cut and plane. Regardless of how wide or narrow the door, the proportions of each component to the entire door are exactly the same.

What’s better yet is you don’t even need a ruler or to know the dimension of the opening. You simply mark the width of the opening on a scrap piece of wood or story stick, use your dividers to divide it into 9 parts and start laying out your door. The idea of not knowing or needing the dimension of a door is hard for modern tradesmen to wrap their heads around, but in the 18th and 19th century this was standard procedure.

Why is this important? These differences in approach explain why modern replacement doors often look so odd in older homes. In an age where everything is standardized (e.g. the width of door stiles and rails), when modern shops build odd-sized doors for older homes the proportions of the door parts are usually off. They just don’t know the proportions governing the dimensions of the door’s various parts and don’t adjust their designs.

Whenever I visit an historic home I take careful measurements of doors, windows, molding and other millwork and determine the proportions of each piece. Then, if I make a hand-made door for a Greek Revival home, I can check the measurements and proportions for doors in similar homes and use them to make the replacement. Not only does my replacement door have appropriate tool marks and construction for the 19th century, its proportions, molding and shape are also correct.

0 Comments